For over a decade Maine Sea Grant has been collaborating with several colleges in Maine to provide $1000 scholarships for undergraduates doing work in Marine Sciences. This doesn’t just mean students doing research, but also students working in communication, education, policy, advocacy, and just about anything you can imagine marine related. This year the application period just opened, and you can see the announcement and the link to download an application here. This scholarship is available to any second and third-year students enrolled at COA (and several other colleges) and the deadline is May 20th. COA and Maine Sea Grant contribute equally to funding the scholarship.

I’ve asked the six current students that are recipients from past years, Wriley Hodge from 2022 and Marina Schnell, Ellie Gabrielson, Katie Culp, Massimo Hamilton, and Emily Rose Stringer from 2023 to give a short student profile and talk about what they have been up to below. The profiles into divided into two posts – this first post focuses on the three students that have been doing work on the school’s island research stations – Wriley Hodge on Great Duck Island, Marina Schnell and Ellie Gabrielson on Mount Desert Rock. Part 2 can be found here.

If you are a COA student and interested in applying for this scholarship, you can talk to any of the current student recipients, or me (Chris Petersen). You can read about the 2021 recipients here, and the marine studies at coa blog has several other posts on past recipients here, here, and here. – Chris Petersen, soon to be retired COA faculty member.

Wriley Hodge ’24. My love for the Gulf of Maine started from a very young age. I spent my summers with my grandparents in Jonesport, a small fishing town in downeast Maine; I remember those summers of exploring tidepools and islands with a very deep fondness. When I came to College of the Atlantic, this love took a new form. I took as many place-based ecology classes as I possibly could, and during the summer of 2021, I began doing seabird research at the Alice Eno Research Station on Great Duck Island.

In 2022, I returned to Great Duck and I began working on an original research project looking at the factors impacting nesting density and distribution of Herring Gulls (Larus argentatus). This research morphed into my senior project at COA, and I continued field work through the 2023 field season. My research is primarily concerned with why we see differences in nesting density and distribution within a single colony. My data collection involved mapping nest locations, recording habitat data, and observing individual birds nesting in different habitats (if you want to learn more about this research, check out this story map!). In 2023, I also had the opportunity to work with Acadia National Park on their seabird islands, and me and a team of fellow students mapped a series of seabird colonies, and worked to band and attach GPS tags to breeding Herring Gulls. While seabird data on Great Duck goes back 25 years, data on Acadia’s seabird islands is relatively scarce; this project is an attempt to expand our understanding of seabird dynamics in the Greater MDI region. It also allowed me to expand the scope of my own research by mapping additional islands. You can learn more about the research on Acadia’s islands here.

Photos above, left to right: An adult herring gull, putting gps tag on a gull, and mapping a gull colony on a Maine island.

I love working in the field, and I think islands are a fantastic place to conduct research. I have really enjoyed being able to mix natural history observations, and modern data analysis techniques to answer interesting questions. I am deeply thankful for Maine Sea Grant, Maine Space Grant, Friends of Acadia, Downeast Audubon, the Barry Goldwater Scholarship for funding my research, and to and numerous professors and mentors, without whom none of this would have been possible.

Marina Schnell ’25

In my very first class at COA, I got tangled in the seaweed, and the intertidal has not let me go. I spent the summer of 2023 at the research station on Mount Desert Rock (MDR) as a student co-manager and continued the intertidal work I began in 2022. I created paintings of 20 intertidal invertebrates and seaweeds, which I will eventually include in a field guide. I also continued recording observations about the overall ecology and species composition in the MDR intertidal, and I found an incredible diversity of organisms, from sea spiders to nudibranchs to brittle stars. I focused on hydroids, a type of marine invertebrate related to jellyfish and sea anemones.

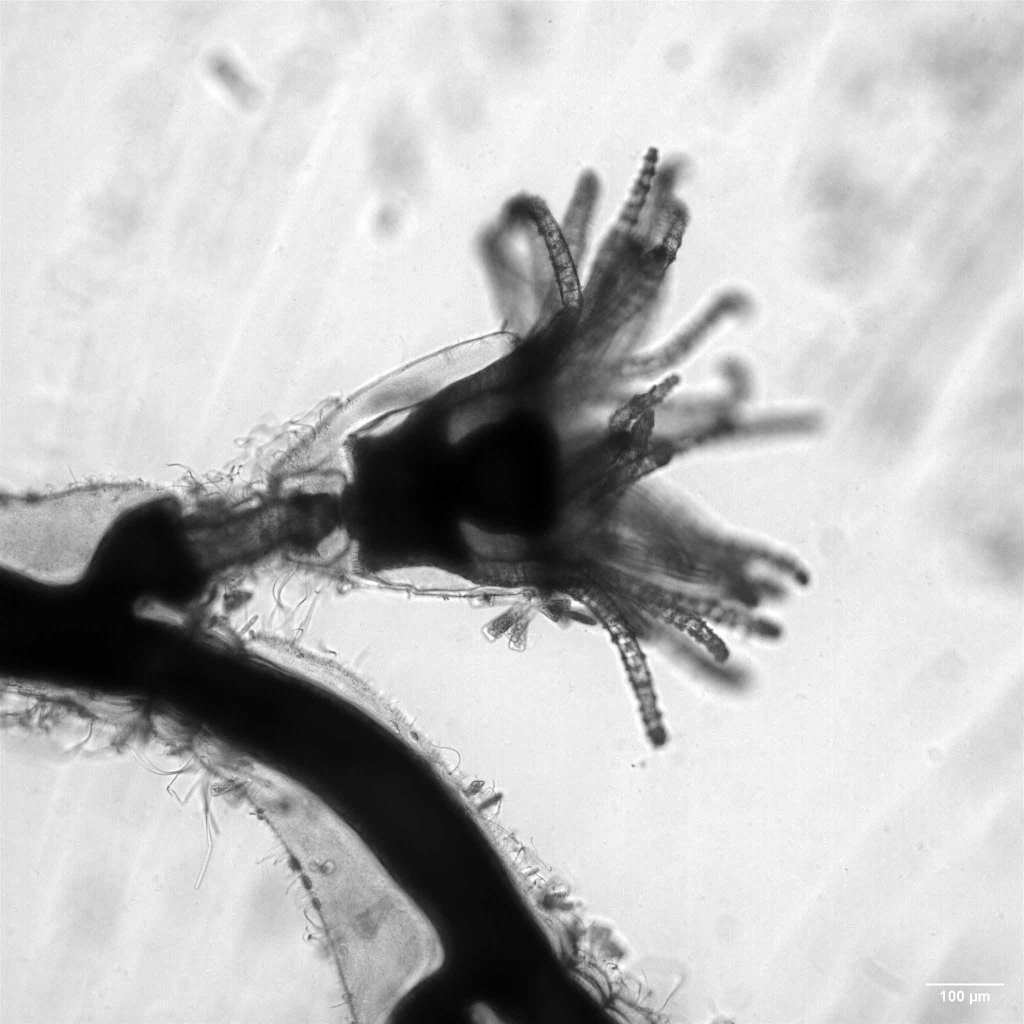

Hydroids are a cryptic and under-studied group of organisms, so my central questions are simple: how many species are there on MDR? How much of the morphological variation I observe is due to differences among species, and how much is due to morphological plasticity within species? MDR is a high-energy environment, constantly battered by waves, but some areas are more protected than others. What might seem to be three different species could actually be one species in three different microhabitats on MDR. Throughout the summer, I scoured the intertidal of MDR for as many types of hydroid as I could find. I recorded details of their habitat and morphology in the field, sketched and photographed each colony under a dissecting microscope, and preserved samples of each colony.

Left to right: Photograph of a hydroid colony taken with the microscope at the MDR field station. A magnified version of another campanularid hydroid, taken with the help of Dustin Updike and Noah Lind at Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory. A small dorid nudibranch, which are typically specialized carnivores, crawling over and probably consuming a different small hydroid species from the family Corynidae, in a MDR tide pool.

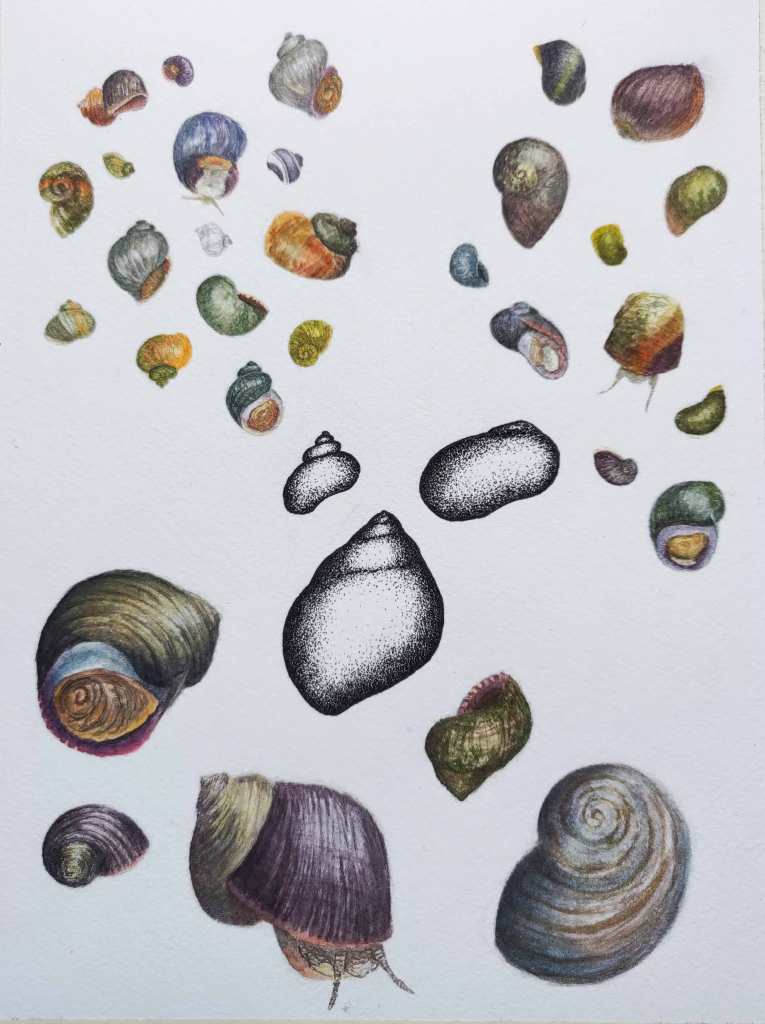

Art has been an important part of my life for many years, sometimes as a respite from my scientific endeavors and sometimes as a complement. I started as a potter, and during my time at COA, I have developed my field sketching and scientific illustration skills. Drawing organisms from life allows me to more fully understand their structures, and it is a way for me to share my appreciation for their incredible beauty and complexity.On the more quantitative side, I’m also looking at overall intertidal community structure on MDR which is focused on the abundance and distribution of the common intertidal animals and algae found there. I’ve been delving into the archive of 7 years of MDR intertidal survey data from the Northeastern Coastal Station Alliance (NeCSA), a collaborative data collection project from multiple field stations throughout the coast of Maine. From 2017 through 2021, the survey on MDR was conducted by Tanya Lubansky and a group of students from the John Bapst Memorial High School, and I organized the survey in 2022 and 2023. I am presenting these results at conferences, summarizing both what we are learning and to summarize the challenges for these types of long-term and citizen-science projects.

Some paintings of intertidal organisms from Mount Desert Rock. An aeolid nudibranch, the most common brown algae in the intertidal, knotted wrake (Ascophyllum nodosum) and rockweed (Fucus spp.), and a sheet of periwinkles (Littorina spp.).

Currently I’m working with my advisor Chris Petersen to try to identify some of these invertebrates, in particular the hydroids. In a Winter 2024 independent study, I took my hydroid specimens from MDR to the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory (MDIBL), where I was able to photograph them under a high-powered microscope. I had hoped that this would allow me to distinguish species using morphology, but this proved difficult, so I worked with Chris to begin genetic analysis of the specimens. The ultimate goal of this process, known as barcoding, is to compare a section of each hydroid’s DNA to a database of known DNA sequences, which will hopefully allow us to identify each sample to the species level. This is an ongoing project!

Pictures below: A common summer behavior – leaning over and staring into tide pools. The reward, a pycnogonid, or sea spider, carrying eggs. Sea spiders are unusual as one of the few groups where male care is the common mode of parental care. In this case the male is carrying small groups of developing eggs, probably from several different females. Below: A mixture of periwinkles (Littorina spp.) and an aeolid nudibranch.

Ellie Gabrielson ’25. I’ve loved the ocean for as long as I can remember. I grew up digging through the mud flat next to my house and spending time in both the frigid Maine and warm tropical waters of Costa Rica. When I arrived at COA, I took every opportunity to spend time at, on, or with the ocean, including taking Sean’s Intro to Oceanography class, joining Osprey crew, etc. The TA for my oceanography class happened to be in charge of the longitudinal copepod study on Mount Desert Rock (MDR) at the time, and boy, that piqued my interest! I decided I would do anything to get out to The Rock. I’m not a field researcher; I do not have the relevant background nor want to pursue it as a career. But I love the ocean, including all the creatures in it, and I also love examining questions of place. I love contemplating how locations become parts of our identities, how living and working on the ocean impacts lives (both human and others), the complexity of island living, and much more.

So, although I’m not a scientist, I was given the opportunity to continue the copepod project with another co-manager, and I was ecstatic. Copepods are microscopic zooplankton essential to all life in the Gulf of Maine. They are a vital source of nutrients for other animals, and some species around the Rock are the favorite snack of the North Atlantic Right Whale. I wanted to know if the status and health of the copepods had anything to do with the Right Whales’ disappearance from the Gulf of Maine. This is surely not a question I can answer alone, but I pondered it frequently while identifying and measuring thousands of individual copepods. This study also involved collecting oceanographic data, such as water temperature and salinity, something I didn’t expect to have so much fun with!

A planktonic copepod under the microscope at Mount Desert Rock, a gull chick in hand, and doing some sampling as part of the oceangraaphy class.

Conducting a 10-week-long study was tedious, hard, and frustrating times. But it was also rewarding and fun, and I learned so much about the world around me and myself. Island living was similarly dynamic, but more than anything, it was purely vibrant with life. To hear the blow of a whale, watch their sleek backs cut through the glassy water, hold baby gull chicks, play the harmonica around a fire, eat pretzels, admire the most unique view of MDI, turn composting toilets, etc., all from 26 miles offshore is crazy. I cherished every second of my time on MDR.

On a more logistical note, the Maine Sea Grant was essential in ensuring I could do this research, as it was an unpaid position. I’m incredibly grateful for the opportunity to do research as an undergrad and for Maine Sea Grant’s generosity, which will propel me through the rest of my studies at COA.

Drawing by Wriley Hodge